Mao Era vs. Deng Era: a China Writers’ Group email thread tells the real story

Pictured above: Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping in 1959, in the midst of the Great Leap Forward, the greatest outburst of industrialization in human history, outpacing the Industrial Revolutions of England, Germany, Japan and the USA.

- China’s capitalist reforms are said to have moved 800 million out of extreme poverty. Data suggest the opposite.

https://phys.org/news/2024-01-china-capitalist-reforms-million-extreme.html

Godfree Roberts (https://www.herecomeschina.com/)

2. Back to Communism and the Liáng piào? (Mao-Era food coupons)

“While access to basic needs recovered during the 2000s, rough estimates for 2018 suggest that the extreme poverty rate remains at roughly the same level as during the 1980s. “

https://phys.org/news/2023-07-china-extreme-poverty-capitalist-reforms.html

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13563467.2023.2217087

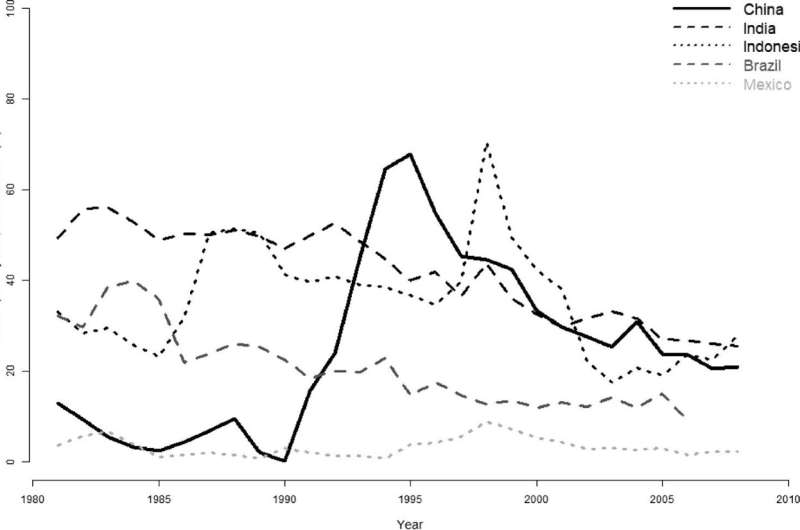

“These estimates indicate that from 1981 to 1990, when most of China’s socialist provisioning systems were still in place, the country’s extreme poverty rate was on average only 5.6 per cent, substantially lower than in capitalist economies of comparable size and income at the time: 51 per cent in India, 36.5 per cent in Indonesia, and 29.5 per cent in Brazil.”

Gavin McGregor (https://seektruthfromfacts.org/gavin/)

3. This runs so counter to what has been thought and so different from the impression that I have. Someone who works in this field needs to make a critique.

John

4. The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994 Hardcover – September 30, 1996. by Maurice Meisner (Author)

Review by William Podmoreon, April 23, 2012, Format: Hardcover

This is a superb study of China under Deng Xiaoping.

Godfree Roberts (https://www.herecomeschina.com/)

Meisner first looks at China’s achievements under Mao. He notes, “From 1952 to the mid-1970s, net agricultural output in China increased at an average per annum rate of 2.5 percent, whereas the figure for the most intensive period of Japan’s industrialization (from 1868 to 1912) was 1.7 percent.”

Meisner writes, “Between 1952 and the close of the Mao era, steel production increased from 1.4 to 31.8 million tons; coal from 66 to 617 million tons; cement from 3 to 65 million tons; timber from 11 to 51 million tons; electric power from 7 to 256 billion kilowatt hours; crude oil from virtually nothing to 104 million tons; and chemical fertilizer from 39,000 to 8,693,000 tons. By the mid-1970s, China was also producing substantial numbers of jet airplanes, heavy tractors, railway locomotives, and modern oceangoing vessels. The People’s Republic also became a significant nuclear power, complete with intercontinental ballistic missiles. Its first successful atomic bomb test was held in 1964, the first hydrogen bomb was produced in 1967, and a satellite was launched into orbit in 1970.”

He praises “the Mao regime’s striking successes in transforming China from one of the world’s most backward agrarian countries into the sixth-largest industrial power by the mid-1970s.”

He observes, “It has often been pointed out that conventional measurements of income and consumption are inadequate indicators of the actual standard of living and the quality of life. It is also necessary to take into account public consumption in such elemental and essential realms as education, health care, sanitation, and welfare provisions for the elderly and the destitute – matters not easily quantifiable in standard economic calculations. In all of these areas the Mao regime achieved great social progress, and by most key social and demographic indicators the People’s Republic compared favorably not only with other low-income countries such as India and Pakistan but also with `middle-income’ countries whose per capita GNP was five times that of China.” Meisner cites Carl Riskin who wrote, “China’s poor emerged from the Maoist era significantly better off than the poor of most other developing countries.”

Meisner then turns to examining China under Deng. He points out, “To no small degree, the agrarian successes of the Deng era capitalized on the economic foundations laid during the Mao era. … Certainly the higher yields obtained on individual family farms during the early Deng era would not have been possible had it not been for the vast irrigation and flood-control projects – dams, irrigation works, and river dikes – constructed by collectivized peasants in the 1950s and 1960s.”

As Riskin noted, “The beginning of the spurt in agricultural growth preceded both the price changes and the more radical decollectivization measures. Total agricultural output surged forward by 8.9 per cent in 1978 and 8.6 per cent in 1979, whereas in early 1980 only about 1 per cent of farm households had adopted any form of HRS [household responsibility system].” Under HRS, individual households owned the means of production – land, capital, machinery and labour power.

Meisner observes, “The old problem of the fragmentation of farming units, which collectivization was partly designed to solve and was largely successful in accomplishing, has reappeared with the return to individual family farming. … This new fragmentation of the land virtually precludes the mechanization of agriculture, which many agronomists believe is the most promising way to achieve significant and sustained progress in future years. … Perhaps the most serious long-term consequence of the Deng regime’s rural reform policies has been the enormous growth of socio-economic inequality in the countryside and the creation of new class divisions which virtually guarantee social conflicts …”

He writes, “With the abolition of the commune system and the commercialization of agriculture, nearly 200 million rural dwellers, about half the total rural workforce, were rendered redundant, unable to subsist on the land.” And, “With the abolition of the communes, the rural social security and health-care systems largely disappeared, and the government has done little to replace them.”

Meisner points out, “It is ironic that just as China’s leaders were most vigorously denying the existence of a bureaucratic ruling class in the People’s Republic, they were introducing policies that were to generate – in an extraordinarily short period of time – a capitalist economy and a bureaucratic bourgeoisie to preside over it. The rapid expansion of market relationships, the enormous growth in foreign trade, the influx of foreign capital, the decollectivization of agriculture, the encouragement of private enterprise of all sorts, and the various forms of decentralization that loosened central control over the economy combined to breed corruption in epidemic proportions and to transform many Communist bureaucrats into quasi-capitalist entrepreneurs …”

He asserts, “As has been true of the histories of all capitalist economies, the power of the state was very much involved in establishing China’s labor market. Indeed, in China a highly repressive state apparatus played a particularly direct and coercive role in the commodification of labor, a process that has proceeded with a rapidity and on a scale that is historically unprecedented.”

He notes, “Frenetic and chaotic industrialization continued to poison the air and water, and further shrank the acreage of land under cultivation. Industrial accidents reached frightening proportions, killing an estimated 20,000 workers annually in the early 1990s, and injuring many more.”

Of China during the `reform era’, Meisner concludes, “The economic gains have been spectacular. The social results are calamitous.” As Marx observed, capitalism is a “social anarchy which turns every economic progress into a social calamity.”

###

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

I remember reading somewhere that Deng said that Mao was 70% right and 30% wrong. Perhaps, it was really meant to say that Deng was 30% right and 70% wrong!

It is true that for non-libertarians, Deng took huge risks and harmed a lot of citizens his gambit of “300 years of capitalism” compressed into one generation.